Premios Nacionales 1940-1969: memoria de un país en construcción

Entre la historia y la memoria, esta exposición reconstruye tres décadas fundamentales del arte venezolano, cuando el Salón Oficial y los Premios Nacionales delineaban, año tras año, la imagen de un país que buscaba reconocerse en sus artistas.

Alirio Rodríguez

En la Galería Freites de Caracas se abre un tiempo detenido. La exposición Premios Nacionales de Pintura 1940-1969 invita a mirar de nuevo un período decisivo en la historia del arte venezolano: aquellos años en que el Salón Oficial y los premios nacionales marcaban el pulso de la modernidad y del gusto institucional.

Héctor Poleo

Durante casi tres décadas, los premios fueron más que una distinción: eran el espejo de un país que buscaba definirse a través de sus artistas. Allí convivían la tradición y la ruptura, el retrato académico y la abstracción incipiente, los nombres que hoy son leyenda y otros que el tiempo ha borrado con discreción.

El Salón Oficial, instaurado en 1940, otorgaba reconocimientos en distintas disciplinas —pintura, escultura, dibujo, grabado y artes aplicadas—, pero esta muestra se concentra exclusivamente en el renglón de pintura, acaso el más revelador de las tensiones estéticas de la época. En esa línea del tiempo —que Sergio Antillano registró con la precisión de un cronista y la pasión de un testigo— puede seguirse la evolución de un lenguaje plástico que se emancipaba lentamente del paisaje y del costumbrismo.

El gran punto de quiebre llegó en la década de los cincuenta, cuando el abstraccionismo geométrico irrumpió con fuerza en la escena venezolana de la mano de Jesús Soto, Alejandro Otero, y más tarde Cruz-Diez, desplazando el centro de gravedad hacia la experimentación óptica y cinética, y redefiniendo para siempre la noción de modernidad.

Armando Reverón

De Armando Reverón a Jesús Soto, de Manuel Cabré a Francisco Hung y de Armando Barrios a Alirio Rodríguez, los premios no solo consagraron trayectorias, sino que abrieron el espacio para pensar lo venezolano desde la forma y el color.

Armando Barrios

Revisitar hoy esas obras, muchas de ellas dispersas en colecciones públicas y privadas, es también reencontrarse con un país que apostaba por la cultura como una afirmación de identidad. La exposición no es una celebración nostálgica, sino un ejercicio de arqueología estética, al mostrar la memoria de un sistema que, con sus virtudes y contradicciones, dio origen al arte contemporáneo venezolano.

Quizás por eso este recorrido no se siente como un regreso, sino como una pregunta: ¿qué lugar ocupa hoy el reconocimiento institucional en la vida de nuestros artistas? ¿Qué sentido tiene la palabra “premio” en un tiempo sin salones, sin jurados, sin consenso?

Entre 1940 y 1969, cada medalla entregada llevaba el peso simbólico de un país en construcción. Hoy, al mirar esas pinturas reunidas bajo la misma luz, entendemos que también nosotros somos herederos de aquella mirada que quiso creer en el arte como destino.

Alejandro Otero

National Awards 1940–1969: Memory of a Nation in the Making

Between history and memory, this exhibition reconstructs three pivotal decades of Venezuelan art, when the Official Salon and the National Awards traced—year by year—the image of a nation learning to recognize itself in its artists.

At the Galería Freites in Caracas, time seems to stand still. The exhibition National Painting Awards 1940–1969 invites us to revisit a decisive period in the history of Venezuelan art—those years when the Official Salon and the National Awards set the tone of modernity and institutional taste.

Régulo Pérez

For nearly three decades, the awards were more than a distinction: they were the mirror of a nation seeking to define itself through its artists. Tradition and rupture coexisted there, as did academic portraiture and the first signs of abstraction—the names that became legend and others that time quietly erased.

The Official Salon, established in 1940, granted recognition across several disciplines—painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, and applied arts—but this exhibition focuses exclusively on painting, perhaps the most revealing of the era’s aesthetic tensions. Along that timeline—which Sergio Antillano documented with the precision of a chronicler and the passion of a witness—one can trace the evolution of a visual language gradually freeing itself from landscape and costumbrismo.

Humberto Jaimes Sánchez

The turning point came in the 1950s, when geometric abstraction burst onto the Venezuelan scene through the work of Jesús Soto, Alejandro Otero, and later Carlos Cruz-Diez, shifting the center of gravity toward optical and kinetic experimentation and redefining the very notion of modernity.

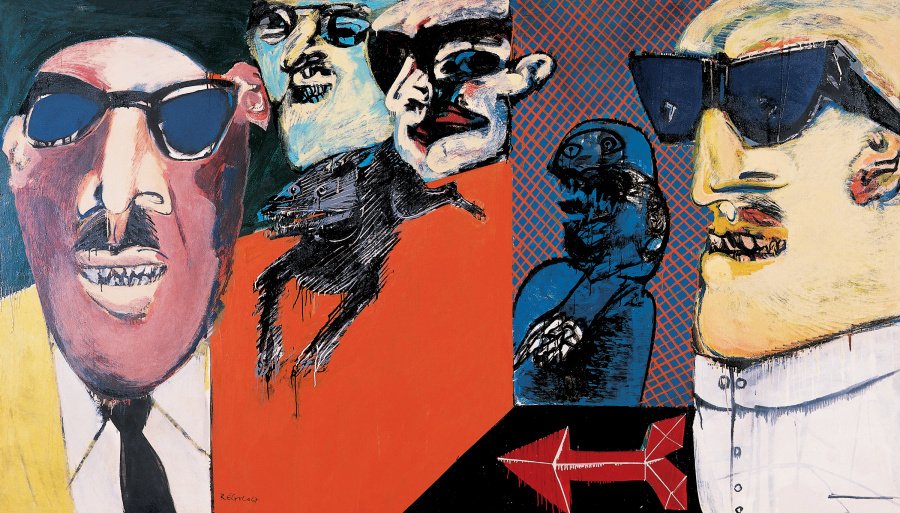

Jacobo Borges

From Armando Reverón to Jesús Soto, from Manuel Cabré to Francisco Hung, and from Armando Barrios to Alirio Rodríguez, the awards did more than honor individual careers—they opened a space to rethink Venezuelan identity through form and color.

Francisco Hung

To revisit these works today, many of them scattered across public and private collections, is also to rediscover a country that once saw culture as an affirmation of its own identity. This exhibition is not a nostalgic celebration but an act of aesthetic archaeology: the recovery of a system that, with all its virtues and contradictions, gave rise to contemporary Venezuelan art.

Perhaps that is why this journey feels less like a return than like a question: What place does institutional recognition hold in the life of our artists today? What meaning does the word award retain in a time without salons, juries, or consensus?

Between 1940 and 1969, every medal carried the symbolic weight of a nation in the making. Today, as we see these paintings gathered under the same light, we realize that we, too, are heirs to that gaze that once believed in art as destiny.

CARACAS D.C. VENEZUELA

Cesar Sasson

Magíster en Curaduría de Arte

coleccionsasson@gmail.com

@coleccionsasson

Ciudad de Panamá – Panamá

Octubre 2025