Este texto no es solo un homenaje, sino también un acto de memoria, escrito en ocasión de su cumpleaños. Un intento por trazar con palabras el perfil sereno y hondo de Félix Perdomo, un artista que vivió —y pintó— en silencio, dejando en cada obra una invitación a detenernos y mirar de otro modo.

Cada vez que pienso en Félix Perdomo, se me impone como una verdad irrefutable la siguiente frase de Marcel Proust: “El arte auténtico no necesita de proclamaciones, cumple su cometido en silencio.” Su vida y su obra transcurrieron entre silencios, sin alardes, sin protagonismos innecesarios, pero dejaron una huella indeleble en quienes tuvimos la suerte de conocerlo y en aquellos que se han acercado a su pintura.

Félix fue un hombre discreto, tímido, reacio a las palabras, pero generoso en sus afectos. Lo conocí en los años ochenta, en la casa de Jorge Stever, en El Hatillo, un lugar que fue para muchos un refugio y un lugar de encuentros. Aquella noche llegó sin anunciarse y, al vernos, se escondió en la cocina, evitando el contacto. Jorge, que siempre supo tender puentes, me habló de él con admiración: me dijo que era un joven que pintaba desde el alma, con una honestidad inusual. Me puso en las manos una carpeta con pequeños dibujos, en los que unos personajes suspendidos en el espacio—que él llamaba “trapecistas”—hacían maromas etéreas. En ellos ya se asomaba la sombra de Giacometti, uno de sus grandes referentes, aunque en ese momento confieso que no supe valorar en su justa medida lo que veía.

Con el tiempo, esa distancia inicial se fue acortando, y nació entre nosotros una amistad profunda y leal. Éramos, como algunos amigos nos bautizaron, “los tres mosqueteros”: Félix, Jorge y yo, unidos por un lazo que superaba el arte y que, en el fondo, nos convertía en una especie de hermandad donde la lealtad era sagrada.

Félix fue un enamorado de su familia, de sus amigos y, de su oficio de pintor. Siempre mantuvo una admiración profunda por Giacometti, Morandi y Matisse, además de su inseparable amigo Jorge Stever. De ellos aprendió la importancia del silencio, del vacío y de la monocromía como lenguaje. Su obra giraba en torno a dos temas esenciales: la presencia a través de la ausencia y la soledad, pero sin melancolía. Sus pinturas transmitían una calma serena, un sosiego que invitaba a la contemplación.

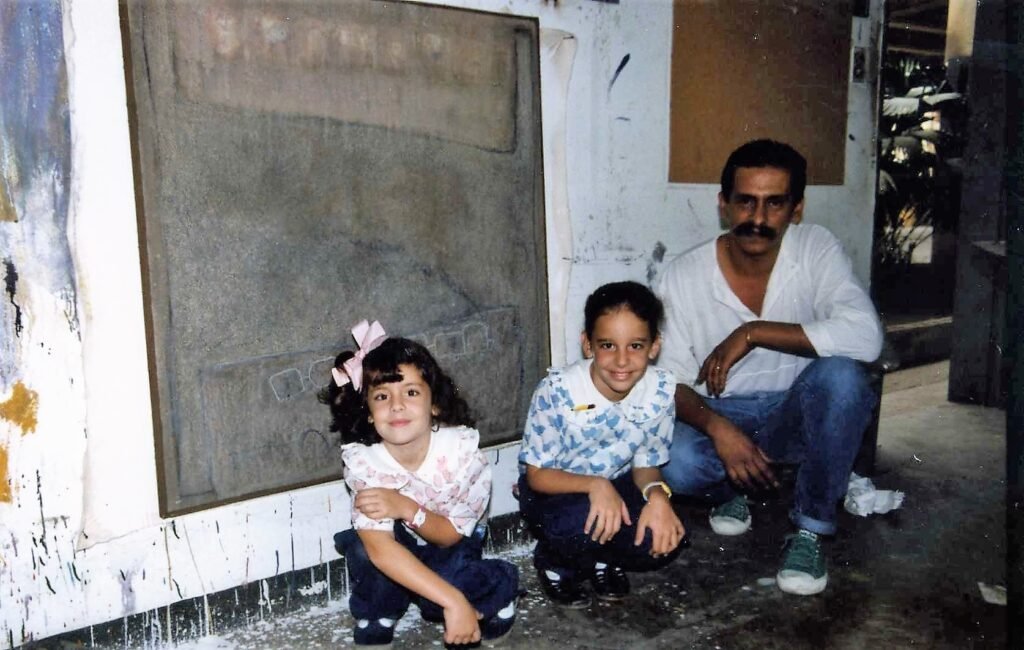

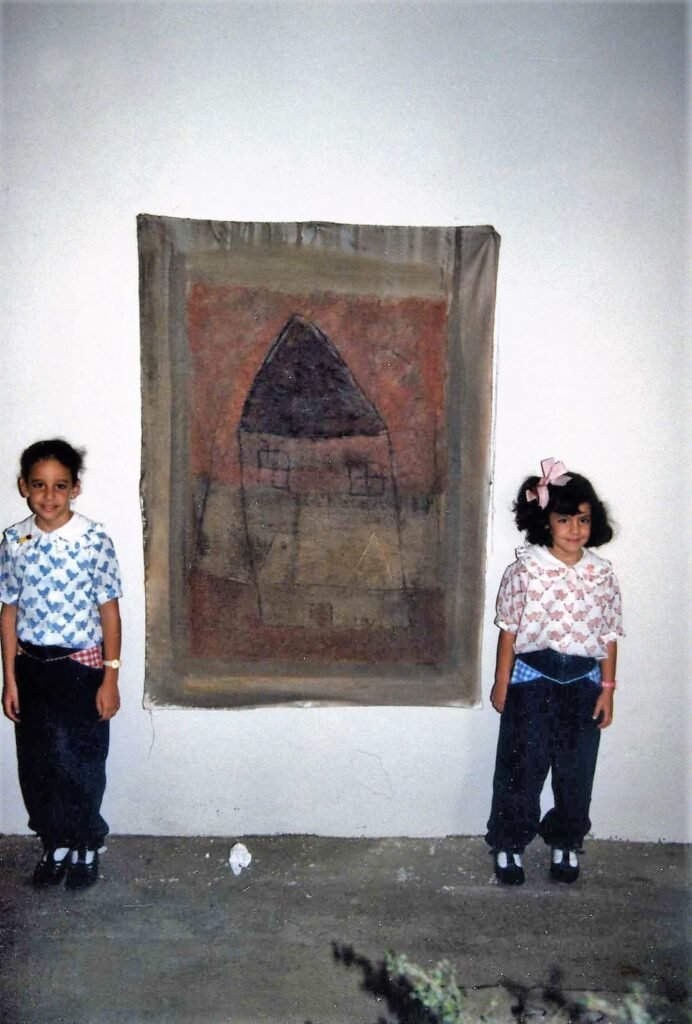

Hermanas Sasson

Con Félix Perdomo en el Pedagógico de Caracas, 1990

En los años noventa, Félix pintó una tela para celebrar el séptimo cumpleaños de la menor de mis dos hijas. Esa pintura monocroma, en tonos ocres, condensaba todo su universo plástico: el uso de materiales humildes como arena, cemento y cola; las texturas provocadas por el sol, la lluvia y las pisadas en su taller, además de los fondos que evocaban muros envejecidos, cargados de una memoria casi arqueológica.

Pero detrás de esa obra hay una historia aún más entrañable. Antes de pintarla, Félix visitó mi casa y se llevó algunos papeles con garabatos de mis hijas. Uno de esos dibujos, una casita hecha por la menor, lo obsesionó. Comenzó a trabajar sobre ella, pero pronto me confesó que, aunque había reproducido la forma, no había logrado capturar el espíritu de la niña. Esa insatisfacción lo llevó a seguir explorando el motivo de la casita, que terminó dando origen a una serie de pinturas que él mismo envió, casi por casualidad, a la convocatoria de la prestigiosa beca del PS1 del MoMA de Nueva York. Contra todo pronóstico, fue seleccionado, convirtiéndose en el primer artista latinoamericano en obtener esa beca.

EL TREN DE MARIANNE

1990

Aquella casita inicial mutó con el tiempo. La pintura fue transformándose hasta que la casa desapareció, dando paso a un gran plano monocromo en el que aparecía apenas la silueta de una mesa con un pequeño trencito dibujado a lápiz, con la inscripción “El trencito de Marianne” y el número siete en alusión a la edad de mi hija. En la parte superior, adheridos a la tela, permanecen algunos de los dibujos originales de la niña, como vestigios de aquel primer impulso.

Así era Félix: capaz de convertir un dibujo infantil en un viaje hacia lo más hondo de la memoria y el arte. Su pintura, a pesar de su austeridad, estaba llena de resonancias históricas. En sus telas convivían las sombras de las Cuevas de Altamira y la luminosidad de Matisse. De este último, había aprendido dos lecciones fundamentales: la alegría del color como fondo y la sutileza del dibujo para crear profundidad sin recurrir a la perspectiva clásica. Por eso, sus obras parecían siempre habitadas por tazas, latas o sillas solitarias, suspendidas sobre grandes superficies planas, en un delicado juego de luces, sombras y líneas invisibles.

Su trayectoria fue fiel a sí misma. Desde sus primeros trapecistas hasta las tazas de café que dominaron sus últimas etapas, su obra giraba sobre un mismo eje, como un reloj detenido que, sin embargo, siempre marca una hora distinta. La circularidad en la pintura de Félix Perdomo es la mejor metáfora de la circularidad del tiempo: se recorre sobre sí misma una y otra vez, pero nunca es exactamente la misma.

Aún recuerdo aquella visita a su taller, poco antes de su partida, cuando lo vi intervenir con pintura blanca una tela terminada. Pensé que intentaba borrar o corregir algo, pero lo que en realidad estaba haciendo era revelando un cielo escondido detrás de la pintura. Allí estaba, como siempre, el horizonte imaginario, las tazas solitarias y ese aire de misterio que sólo él sabía convocar. A veces, la vida es así: nos pasamos años sin ver el cielo que tenemos delante.

Félix partió en un silencio tan profundo como el que marcó su obra. Durante ocho semanas, lo acompañamos en la clínica, esperando una mejoría que nunca llegó. Su muerte prematura dejó un vacío inmenso, pero también la certeza de que su pintura seguirá allí, como un cielo oculto, esperando que alguien alce la mirada y lo descubra, como quien redescubre a un viejo amigo.

Hoy, cada vez que pienso en él, vuelvo a aquella frase de Proust que él mismo parecía encarnar: el arte auténtico no necesita de proclamaciones, cumple su cometido en silencio. Félix Perdomo, con su vida, su amistad y su obra, nos lo enseñó para siempre.

Félix Perdomo

Fotografía Mariano Esquivel

Félix Perdomo, The Silence That Speaks

This text is not just a tribute; it is also an act of remembrance, written on the occasion of his birthday. An attempt to trace with words the serene and profound profile of Félix Perdomo, an artist who lived—and painted—in silence, leaving in each of his works an invitation to pause and see the world differently.

Every time I think of Félix Perdomo, this phrase by Marcel Proust imposes itself on me as an undeniable truth: “True art needs no proclamations; it fulfills its purpose in silence.” His life and work unfolded amid silences—without fanfare, without unnecessary protagonism—but they left an indelible mark on those of us who had the fortune to know him, as well as on those who have approached his art.

Félix was a discreet, shy man, reluctant to speak, but generous in his affections. I met him in the 1980s at Jorge Stever’s house in El Hatillo, a place that served as a refuge and meeting ground for many. That night, he arrived unannounced and, upon seeing us, hid in the kitchen, avoiding contact. Jorge, who always knew how to build bridges, spoke of him with admiration. He told me Félix was a young man who painted from the soul, with unusual honesty. He handed me a folder of small drawings, where some figures—whom Félix called «trapeze artists»—performed ethereal acrobatics, suspended in space. In those drawings, the shadow of Giacometti, one of his great artistic references, was already present, although I confess that, at the time, I couldn’t fully appreciate what I was seeing.

Over time, that initial distance dissolved, and a deep, loyal friendship was born between us. Some friends even nicknamed us “The Three Musketeers”: Félix, Jorge, and I, bound by a bond that transcended art, a kind of brotherhood where loyalty was sacred.

Félix was a devoted lover of his family, his friends, and above all, his craft as a painter. He always held deep admiration for Giacometti, Morandi, and Matisse, in addition to his inseparable friend Jorge Stever. From them, he learned the importance of silence, emptiness, and monochromy as a language. His work revolved around two essential themes: presence through absence, and solitude—though never tinged with melancholy. His paintings conveyed a serene calm, an invitation to contemplation.

In the 1990s, Félix painted a canvas to celebrate the seventh birthday of my youngest daughter. That monochrome painting, in ochre tones, distilled his entire artistic universe: the use of humble materials like sand, cement, and glue; textures shaped by sun, rain, and footsteps in his studio; and backgrounds evoking weathered walls, laden with a nearly archaeological sense of memory.

But behind that work lies an even more endearing story. Before painting it, Félix visited my home and took some papers with my daughters’ drawings. One of those drawings—a little house made by the younger one—haunted him. He began working on it but soon confessed to me that, although he had replicated the form, he hadn’t captured the spirit of the child. That dissatisfaction led him to keep exploring the image of the little house, which eventually gave rise to a series of paintings that he submitted—almost by chance—to the prestigious PS1 fellowship competition at the MoMA in New York. Against all odds, he was selected, becoming the first Latin American artist to receive that fellowship.

Hermanas Sasson

al lado del cuadro de la casa, 1990

That initial little house evolved over time. The painting transformed until the house itself disappeared, giving way to a large monochrome plane where only the silhouette of a table remained, with a small train drawn in pencil, inscribed “Marianne’s Little Train” with the number seven on two of its cars, alluding to my daughter’s age. At the top of the canvas, some of her original drawings remained attached, as vestiges of that first creative impulse.

That was Félix: capable of turning a child’s drawing into a profound journey through memory and art. Despite its austerity, his painting was filled with historical resonances. His canvases evoked everything from the shadows of the Altamira Cave paintings to the luminosity of Matisse. From the latter, he had learned two fundamental lessons: the joy of color in the background and the subtlety of drawing to create depth without resorting to traditional perspective. That’s why his works always seemed inhabited by solitary cups, cans, or chairs, resting on vast flat surfaces, delicately balanced by light, shadows, and invisible lines.

His career remained true to itself. From his early trapeze artists to the coffee cups that dominated his later years, his work kept revolving around the same axis—like a stopped clock that, paradoxically, always shows a different time. The circularity of Félix Perdomo’s painting is the perfect metaphor for the circularity of time: it moves over itself again and again, but it is never exactly the same.

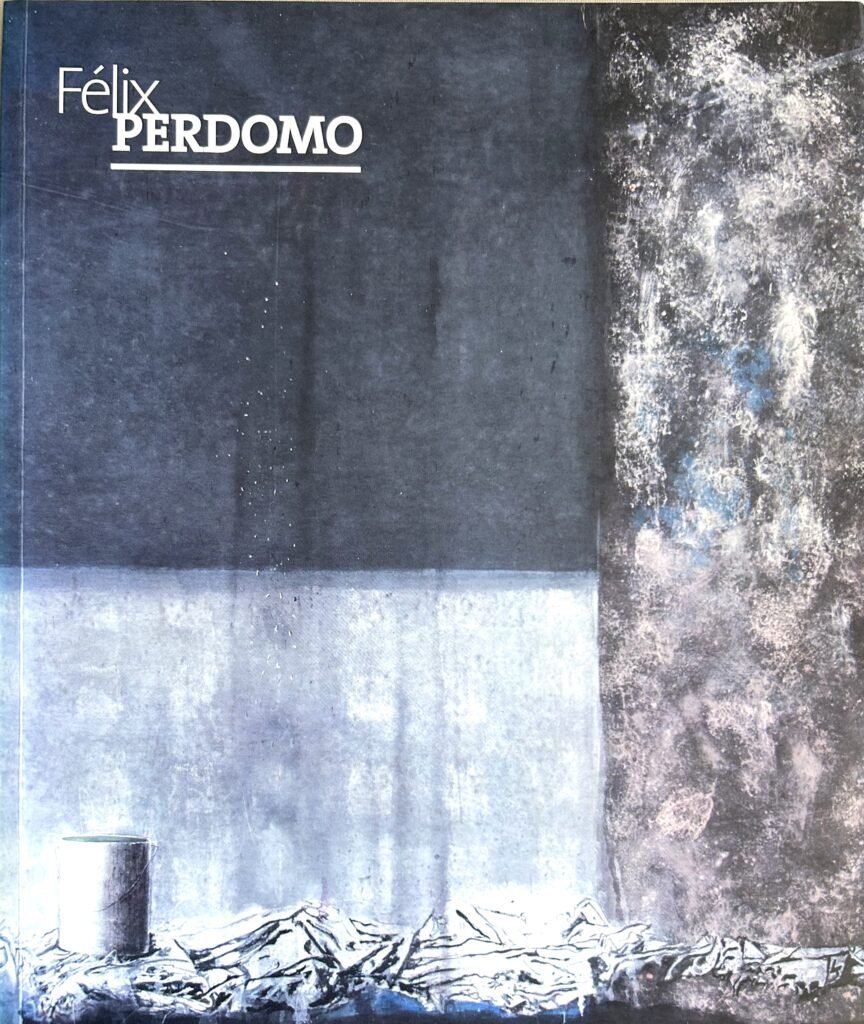

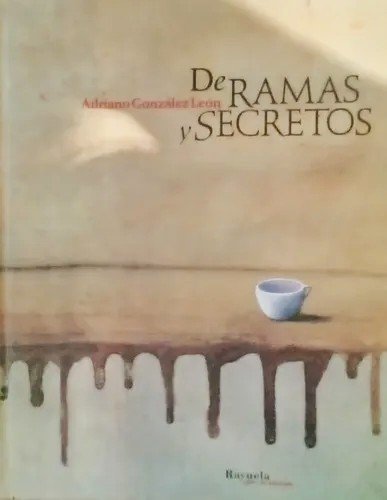

Portada del libro publicado por la Galería Arte Florida

I still remember a visit to his studio, shortly before his passing, when I saw him applying white paint over a finished canvas. I thought he was trying to erase or fix something, but in reality, he was revealing a hidden sky beneath the painting. There it was, as always—the imaginary horizon, the solitary cups, and that aura of mystery that only he knew how to summon. Sometimes life is like that—we spend years unable to see the sky that’s been in front of us all along.

Félix departed in a silence as deep as the one that marked his work. For eight weeks, we stayed by his side in the clinic, waiting for a recovery that never came. His premature death left an immense void, but also the certainty that his painting remains there, like a hidden sky, waiting for someone to lift their gaze and discover it—like finding an old friend once again.

Today, every time I think of him, I return to that phrase by Proust that he himself seemed to embody: true art needs no proclamations; it fulfills its purpose in silence. Félix Perdomo, through his life, his friendship, and his art, taught us that forever.

Cesar Sasson

Magíster en Curaduría de Arte

coleccionsasson@gmail.com

@coleccionsasson

Ciudad de Panamá – Panamá

Julio 2025