En el centenario del nacimiento de Elsa Gramcko, este texto rinde homenaje a la artista desde una vivencia íntima. Un viaje a Borburata en 1980, guiado por la ilusión de encontrar una obra suya, se convierte en una travesía personal que descubre, entre el silencio de la costa y las ruinas del puerto, una revelación inesperada. Entre la memoria del arte y el inicio de la vida, se traza aquí una línea sensible entre lo que buscamos y lo que encontramos.

En 1980, con apenas treinta años de edad y todos los sueños intactos. Era un joven ingeniero, casado, con un trabajo estable en una empresa que acababa de ganar una licitación para realizar unas obras en un club de playa propiedad de Maraven, ubicado en Borburata, en las afueras de Puerto Cabello. Aquel lugar era una curiosa mezcla: por un lado, base industrial donde atracaban cargueros para recoger productos químicos; por el otro, un refugio vacacional para los empleados de la empresa. Una rareza que contaba con apenas tres casas, un muelle, una hermosa playa, y un silencio que se extendía más allá del horizonte.

Cuando supe que me enviarían allí, lo primero que pensé —y esto no deja de parecerme hermoso y a la vez casi ingenuo— fue en Elsa Gramcko. No en la persona, por supuesto, sino en la posibilidad de encontrar una obra suya. Dado que había nacido en Puerto Cabello, y para mí, que comenzaba a despertar a la pasión por el arte, la idea de descubrir una pintura olvidada en algún rincón, o de escuchar su nombre en boca de alguien del pueblo, era una ilusión secreta, como quien busca un relicario en medio del polvo.

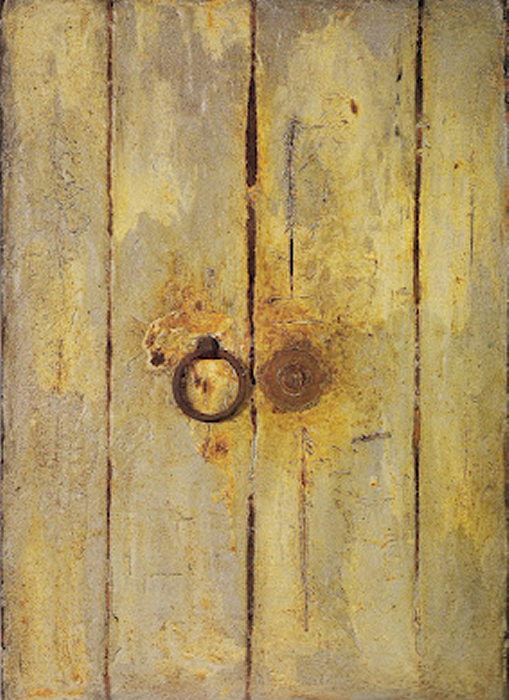

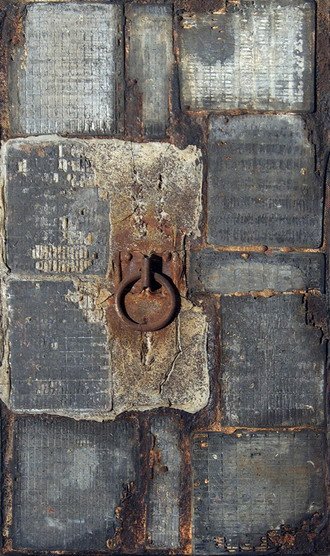

Elsa Gramcko, la alquimista de la materia, la que transformaba óxido y madera en lenguaje. Pintora, escultora, creadora de un universo propio donde lo poético y lo ruinoso se funden. Su obra transitó desde la abstracción lírica hasta esos ensamblajes ásperos y potentes que desafiaban los límites entre lo que se cuelga en la pared y lo que se recoge del suelo. En 1968 había recibido el Premio Nacional de Artes Plásticas en el Salón Oficial de Arte Venezolano y, dos años antes, se había convertido en la primera mujer en ganar el Salón D’Empaire en Maracaibo. Todo ello la hacía —y la sigue haciendo— una figura mayor del arte venezolano del siglo XX.

Pero no encontré a Elsa. Ni su obra. Ni una sola mención. Lo que hallé fue una ciudad portuaria herida, como una postal en descomposición, con edificios venidos a menos y calles que hablaban en voz baja. Esa Puerto Cabello de 1980 me dolió, porque parecía llevar sobre sí una costra de olvido que nada tenía de artístico. Las ruinas, en su caso, no eran parte de una obra de arte: eran reales, eran tristes.

Sin embargo, algo ocurrió. En medio de esa búsqueda fallida, una noticia me sorprendió como una pincelada inesperada en un lienzo neutro. Un día, llamando por teléfono a mi esposa desde aquella playa desierta, me contó que había ido al médico y que estaba embarazada. Nuestra primera hija venía en camino.

Mi búsqueda por una obra de Elsa Gramcko terminó en otra clase de hallazgo: la certeza de que algo nuevo se estaba gestando. No encontré arte colgado en ninguna pared de aquella ciudad, pero la vida —tan sabia como la propia Gramcko— me entregó una obra en construcción: mi primera hija. Curiosamente, ella nació un 8 de abril, apenas un día antes del cumpleaños de Elsa. Desde entonces, al recordar a una, inevitablemente pienso en la otra.

Hoy, al cumplirse cien años del nacimiento de Elsa, vuelvo a pensar en aquella historia. Y quizás ahora comprendo mejor su obra. Sus ensamblajes, como mi recuerdo, son también fragmentos de algo más grande: una historia personal tejida con óxido, arena y luz. Un gesto de memoria que, aunque no se cuelgue en una galería, perdura.

A Day Before Elsa

On the centenary of Elsa Gramcko’s birth, this text pays tribute to the artist through a personal experience. A trip to Borburata in 1980, driven by the quiet hope of finding one of her works, becomes a journey of self-discovery. Between the silence of the coast and the ruins of the port, an unexpected revelation emerges. Between the memory of art and the beginning of life, a subtle line is drawn here—between what we search for and what we end up finding.

In 1980, I was just thirty years old, with all my dreams still intact. I was a young engineer, married, with a stable job in a company that had just won a bid to carry out some construction work at a beach club owned by Maraven, located in Borburata, on the outskirts of Puerto Cabello. That place was a curious mix: on the one hand, an industrial base where cargo ships came to collect chemicals; on the other, a vacation retreat for the company’s employees. A strange little enclave with barely three houses, a pier, a beautiful beach, and a silence that stretched beyond the horizon.

When I learned I would be sent there, the first thing I thought — and this still seems both beautiful and almost naïve to me — was of Elsa Gramcko. Not the person, of course, but the possibility of finding one of her works. Since she was born in Puerto Cabello, and as I was just beginning to awaken to a passion for art, the idea of discovering a forgotten painting in some dusty corner, or hearing her name spoken by someone in town, became a secret hope, like searching for a relic buried in the dust.

Elsa Gramcko — the alchemist of matter, the one who transformed rust and wood into language. Painter, sculptor, creator of a world where the poetic and the ruined came together. Her work evolved from lyrical abstraction to those rough and powerful assemblages that challenged the boundaries between what hangs on a wall and what is picked up from the ground. In 1968, she received the National Prize for Visual Arts at the Official Venezuelan Art Salon, and two years earlier, she had become the first woman to win the D’Empaire Salon Prize in Maracaibo. All of this made her — and still makes her — a towering figure in twentieth-century Venezuelan art.

But I did not find Elsa. Nor her work. Not even a mention. What I found was a wounded port city, like a postcard in decay, with crumbling buildings and streets that spoke in a low voice. That Puerto Cabello of 1980 pained me, because it seemed to carry a crust of forgetfulness that had nothing artistic about it. The ruins there were not part of any artwork; they were real, and they were sad.

And yet, something happened. Amidst that failed search, a piece of news surprised me like an unexpected brushstroke on a blank canvas. One day, calling my wife from that deserted beach, she told me she had gone to the doctor — she was pregnant. Our first daughter was on her way.

My search for a work by Elsa Gramcko ended in another kind of discovery: the certainty that something new was taking shape. I didn’t find any art hanging on the walls of that city, but life — as wise as Gramcko herself — gave me a work in progress: my first daughter. Curiously, she was born on April 8th, just one day before Elsa’s birthday. Since then, whenever I remember one, I inevitably think of the other.

Today, one hundred years after Elsa’s birth, I find myself thinking back on that story. And perhaps now I better understand her work. Her assemblages, like my memory, are fragments of something greater: a personal history woven with rust, sand, and light. A gesture of remembrance which, though never hung in a gallery, endures.

Cesar Sasson

Ciudad de Panamá – Panamá

Abril 2025